Site

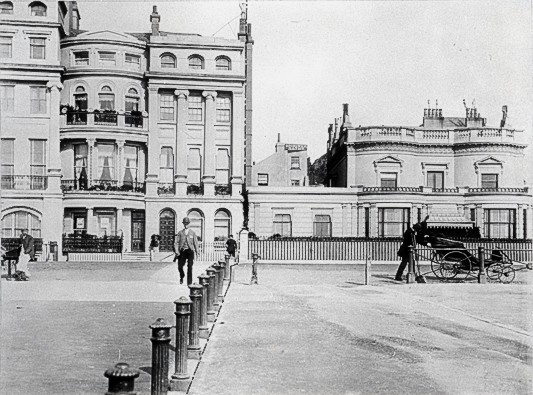

The site was a flood-prone wilderness until the construction of the western esplanade between 1825 and 1834. This massive enterprise, engineered by the architect Amon Henry Wilds, transformed it into one of the most desirable pieces of real-estate on the south coast of England. At the same time the existing groynes stabilising the shingle beach, were repaired and improved and, thus protected from high tides and winter storms, the site became suitable for spectacular buildings.

This was, of course, Amon Henry Wilds’ whole intention, and working together with his father Amon Wilds and architect Charles Busby the noble Brunswick Terrace became the first construction project to take advantage of it. It was a stunning success, the area became known as “West Brighton”, the sea-side retreat of choice for the wealthy and fashionable throughout the 19th Century.

Embassy Court itself is adjacent to Brunswick Terrace and stands on the site of a relatively undistinguished two storey villa known as Western House, completed in 1830. The building was once home to a Lady Hotham and, so it is said, Vesta Tilley, the music hall entertainer and male impersonator whose character “Burlington Bertie” made her an international star. Western House is chiefly remembered for its last owner the reclusive and possibly paranoid newspaper magnate William Waldorf, the first Viscount Astor, who died there in 1919. Western House was demolished in 1930 and for several years, the vacant plot was used for a small car track and miniature golf course.

The eastern and northern parts of the site occupy 1-4 Western street which once included H. Buggins’ Brunswick Baths built to service the fashionable residents of Brunswick Terrace and the area now known as Brunswick Town. The north western edge of the site is dominated by St Andrew’s church, a minor masterpiece by Charles Barry architect of the Houses of Parliament.

The early 1930s were eventually to see the same conditions as those of the 1830s. In the aftermath of economic chaos, a depressed labour market and cheap raw materials brought about a housing boom. And a new, self-confident and forward looking mood had taken root along with it. Maddox Properties, a London based development company acquired the site and set about creating something that would capture the spirit of the new age – a robust architectural statement in the latest style that would appeal to the most fashionable tastes in contemporary living. Amon Henry Wilds could only have approved, if not of the architectural style then certainly the sentiment.

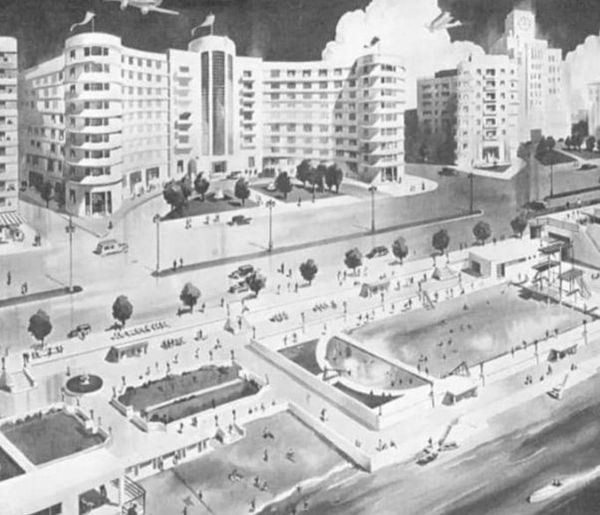

The architectural contract for Embassy Court may have been awarded in open competition since there was at least one alternative design for the site published in 1933. The contract was eventually given to Wells Coates, one of the most capable and committed architects of the Modernist Movement in the UK.

The 1934 Fred Astaire & Ginger Rogers film ‘The Gay Divorcee’ is set in Brighton. The set design is based on plans they were sent by Brighton mayor Henry Carden. His plans were to demolish Palmera & Brunswick & replace with high style Art Deco buildings, think Miami think Embassy Court. Don’t forget at the time the squares were quite run down, full of boarding houses. This image part of the proposed design & what the hotel in the film is based on. As you can see the sunken gardens were the only part of the design completed; Embassy Court is just visible to the far left.

Plan and construction

The plan is a simple L-shape about 44 ft deep wrapping around the seafront to Western Street. An arrangement with the local authority allowed the elevation to rise to eleven storeys high, including a spacious roof terrace. A typical floor contains 7 flats, 6 of which are accessed directly from the lift lobbies on each floor. The flats vary in layout with 1, 2 or 3 bedrooms. The 9th and 10th floors contain some of the first penthouses in the UK. These are smaller and set back from the main frontage with much broader balconies than those on the lower floors.

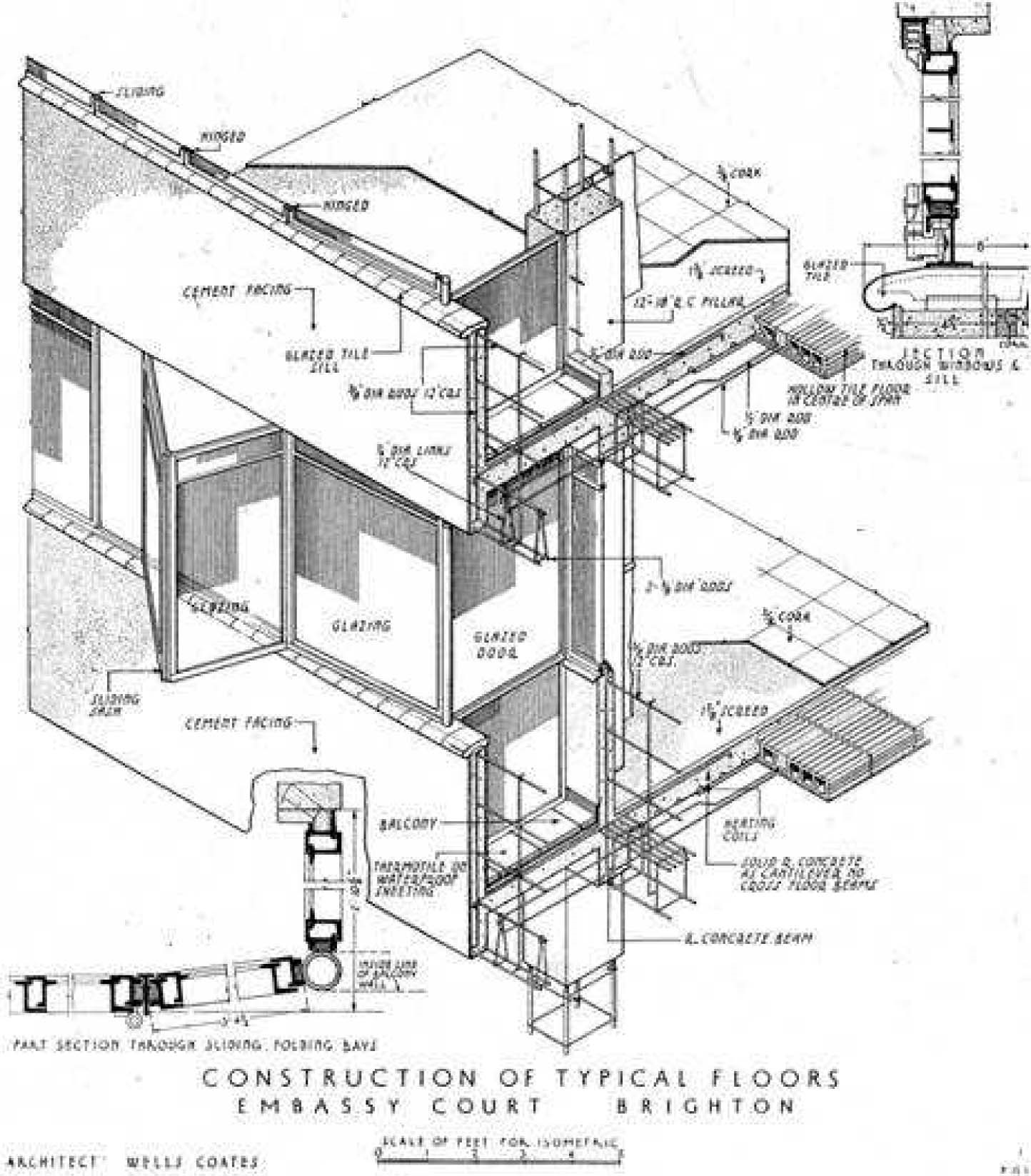

Embassy Court is constructed entirely from reinforced concrete with different grades of reinforcement used depending on whether the elements are load-bearing or not. By the 1930s there were many techniques available for utilising this remarkably versatile material. The architect, Wells Coates, first proposed a diagonal beam grid system, a technique common in Continental civil engineering. This would have provided continuous floors of minimum thickness and free design of interior partitions. Its inventor, a Dr Szego of Budapest visited Coates at the design stage to study the architect’s use of it at Embassy Court. Unfortunately, Brighton Council refused to allow it. The result was a more conventional reinforced concrete frame similar to that used the following year by the architect Berthold Lubetkin at Highpoint II in north London.

The lift shafts and end staircases were designed as groupings of monolithic reinforced concrete stanchions providing strength and stability. Between these elements a grid of light columns was raised supporting three lines of longitudinal beams integrated into the external walls and a central service zone of ducts and cupboards. The floors spanned from beam to beam forming these three elements into a single unified structure of reinforced concrete which was poured in situ. Balconies and walkways are cantilevered on the exterior beams with solid concrete counterbalancing for about three feet internally. The cantilevering is stabilised by the shape of the block and by the three stairwells at the rear. The interior floors are of a hollow block construction into which heating coils were cast for space heating. Integration of structure and services in the building was a core part of Coates’ “Unity of Design” principle.

[Citations: Alan Phillips Architects with Matthew Lloyd, Embassy Court, Feasibility Study, 1998; Zackiewicz Partnership, Report on the Reinforced Concrete Frame 1993]

Innovative features and design

Embassy Court was a showcase for the idea of the “minimum flat”. The Modernist layout of plain surfaces and masses provided for levels of comfort and amenity that were exceptional for their day. Features included under-floor central heating and constant hot water fed from boilers in the basement to bathrooms, kitchens and the washbasins in the main bedrooms. Built-in electric fires, purpose-designed by the architect, provided additional heat. There were telephones in every flat. And in the 1930s its space-saving, fitted kitchens with integral cookers and fridges were almost unheard-of innovations.

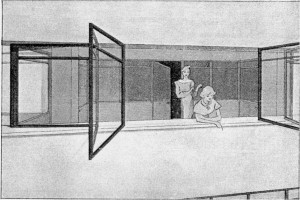

Sunshine and fresh air were provided by sliding and folding “Velux” windows installed along all the frontages. These windows opened like concertinas and when combined with the positioning of French windows this meant that large parts of the front of the flat could be opened to form one almost continuous balcony open to the sun and air.

In the main rooms an ingenious arrangement of interior glass partitions formed what were known as “Sun Parlours”. These trapped warming sunlight in the winter and in summer could protect the rest of the interior from too much fresh air blowing through the flat when the windows were open.

The electric fires, mirrors, bath taps, shower heads and other fittings such as carpets, rugs and furniture were all designed for Embassy Court, many by the architect himself. It was intended as a true Modernist expression of “Design for Living”. The life that would be lived here was to be as open, as inspired and purposeful as the beautiful building in which it was lived.

Embassy Court was greeted with fascination by the Brighton public and acclaim by the architectural press. Criticism was mild, yes the balconies are a little too narrow and, in the flats, the hallways are a little too dark, however, Coates’ stylistic verve carried the day. Charles Reilly, one of the most important influences on British architecture before the Second World War said of it:

“Here at Brighton […] rises this tall graceful building with its long clean lines, vertical as well as horizontal, its fragile looking romantic staircases with landing above landing cantilevered out against the sky and, night and day, thrilling one to the marrow.”

Decline

Reinforced concrete is not as durable as it looks. If left unprotected, it is prone to various forms of contamination which in turn give rise to corrosion in the steel bars embedded within it. These steel bars give reinforced concrete its strength. Rust expands along them forming cracks deep inside the concrete. Eventually these cracks reach the surface, allowing water and air to penetrate more easily and form more rust. A rust-stained hairline crack is the first visible symptom. If left unchecked for long enough serious structural damage can result.

Steel windows can have similar effects. If not properly protected against the environment the corroding steel frames will expand forming cracks in their concrete settings and in glass windows themselves.

Photographs of Embassy Court prior to the restoration show classic examples of both of these types of decay. Along the frontages on Kings Road and Western Street the concrete was protected by a coat of render. Here the main damage was caused by rusting steel windows. Rust damaged the settings allowing water to penetrate between the render and the concrete substrate. Windows fell out on two occasions in the early 1990s forcing the erection of scaffolding around the lower floors to protect passers-by. Gaps in the render around the windows can clearly be seen where pieces of it had either disintegrated or been hacked off to avoid danger to the public.

Serious window damage was common in many parts of the building. But at the rear, rusting reinforcing bars created the classic symptoms of cracked and rust-stained concrete. Small pieces of concrete regularly fell from the side of the building. In some places the concrete looked as if it had been attacked by machine gunners. Perhaps this was the reason for the building’s sardonic nom de guerre; “Beirut” first coined in 1993. The name stuck until the restoration of 2004.

All reinforced concrete buildings are vulnerable to some or all of these problems. But today modern polymer paints and electrolytic techniques provide easier protections and remedies. All that is required is sufficient care and attention. At Embassy Court a preventative regime is in place and problems can be detected early enough for inexpensive repairs to be possible where required.

The plain masses of the modernist interiors were achieved by concealing a large part of the plumbing and hot water systems within the concrete frame itself. More or less all this pipe-work was made from un-galvanised iron and a survey in 1994 concluded that most of it had deteriorated to the point where replacement was the only option.

The symptoms were painfully obvious throughout the following decade. Leaks, damp, drips and stains seemed to appear almost at random throughout the building. Leaks were a major source of dilapidations to interiors. Ceilings acquired holes, plasterwork, carpets and decorations were ruined.

Leaks in embedded pipe work were both difficult to trace and hard to fix. They frequently required much hacking out of concrete before the source of the problem could be determined. However, successive managing agents before the renovation did their best in circumstances that were all but impossible. Pipes were patched up and refurbishments made. Despite everything the vast majority of the flats remained habitable.

Nothing will ever fully prevent leaks. However the restorations of 2004-5 provided solutions to important parts of the problem. The water tanks on the roof were decommissioned and all the main components of the common water services were decommissioned. New services were routed via three of the six lift shafts and connected to the flats via the lift lobbies. The building is now easier to maintain but it is an on-going battle against the elements and the passing of time.

Restoration 2004-2005

Restoration of the building took place in 2004-5 and was a comprehensive repair of the fabric, structure and all of the common parts and included replacements, overhauls or upgrades of all the common services.

The Major Works included:

- Repair of the entire concrete fabric and renewal of all external rendered finishes.

- Replacement of all windows with new specialist powder coated galvanised windows.

- Replacement of the hot water system with new individual boiler systems to each flat.

- Removal of the roof level water tanks and provision of a pumped water system.

- Cleaning repair and/or replacement of all external plumbing and rainwater pipework.

- Installation of new fire alarm system to common parts.

- Renewal of front doors to the original 1936 design.

- Replacement of electrical mains systems to common parts and renewal of lighting.

- New duct for telephone cables.

- Renewed lighting protection system.

- Renewal of entry door system.

- Overhaul and upgrading of passenger lifts.

- Repair and renewal of asphalt roof surfaces, coating with solar reflective paint.

- Preparation and redecoration of all previously decorated surfaces.

- Repair and renewal of all exterior handrails and balustrading.

- Application of a new waterproof surface to exterior walkways.

- Repair and replacement of tiled sills on front balconies.

- Resurfacing vehicle access ramp.

- Replacement of all signage.

- False ceilings to conceal new services.

The Concrete Repairs

The Concrete repairs were carried out by one of the leading specialists in the field; Makers Ltd. The entire concrete surface was grit-blasted to remove paint and loose render. This was followed by a detailed survey of the condition of the concrete. It was hammer tested and sampled at regular intervals for carbonation and chloride contamination. Electronic tests were made to assess the depth of reinforcement.

All concrete designated as defective was chipped out. Where corroded reinforcement was found it was either grit-blasted to remove rust scale and other corrosion products or, where necessary replaced. The surfaces were treated with a corrosion inhibitor, and repaired using techniques to ensure proper compaction and bonding.

The whole surface was then re-rendered with sand and cement to match the original render. Three coatings were then applied, a levelling mortar, a SikaGard primer and finally a flexible “elastomeric” anti-carbonisation paint. These latter finishes made the concrete very considerably more resistant to the most common sources of deterioration and corrosion than it had been at any time in its life.

Window and metal door replacement

All the old Critall steel framed glazing was removed and new windows and doors were purpose made to the exact patterns of the originals. (The doors being those from the flats to the exterior balconies). The steel frames were rust-proofed after manufacture using “hot dip” galvanisation and coated with uniform polyester paint powder. Some leaseholders took the opportunity to replace the casement windows in the main bedrooms with casement doors so that the bedrooms could open onto the balconies. 14mm double glazing was used in the windows and doors in the flats, windows in other parts of the block were single glazed.

Many of the window settings were damaged by corrosion in the old window frames. General repairs to the concrete fabric were carried out first and then the windows removed. If repairs to the surrounds were required then temporary screens were erected inside the flats. Repairs to the window surrounds could then be made and new windows installed prior to the final application of levelling and protective coatings to the exterior concrete fabric.

Window replacement was probably the most difficult and invasive process of the whole restoration programme, especially since Embassy Court’s flats were in full occupation throughout the refurbishment.

Hot Water System

The old system of basement boilers and integral risers was drained and decommissioned. Three of the six lift shafts were given over to the installation of individual gas boilers for each adjacent flat with flues onto the open walkways. New hot water pipes were installed on the roof of the lift lobbies to connect the individual boilers to the flats and hidden above a false ceiling. This system was the overwhelming choice of leaseholders, a similar system was adopted for the refurbishment of Wells Coates’ Isokon flats in Hampstead.

Cold Water System

The original system of roof tanks and integral pipework was drained and, where possible, removed. An entirely new system was installed including, on the lower ground floor, glass reinforced partitioned plastic water tanks and four pumps providing constant water pressure through risers in the three decommissioned lift shafts and connected to the flats via the roof spaces in the lift lobbies. All water pipes are in insulated copper.

Rainwater and Soil Pipe replacement

Many of the rainwater drainage and soil pipes were replaced on a like for like basis using cast iron pipework. New joints to services in the flats were also provided in cast iron or copper.

Further Works to Date

Since the major refurbishment, there has been a continuous programme of redecoration and restorative works to maintain the integrity of the building. The facades and terraces have been repaired and repainted, balconies have been resurfaced, walkways have been sealed and the common parts are repainted on a rolling basis by our maintenance team.

The onslaught of the south westerly storms create challenges in keeping the flats dry and pristine so a programme of phased major works is being developed for delivery over the next few years.