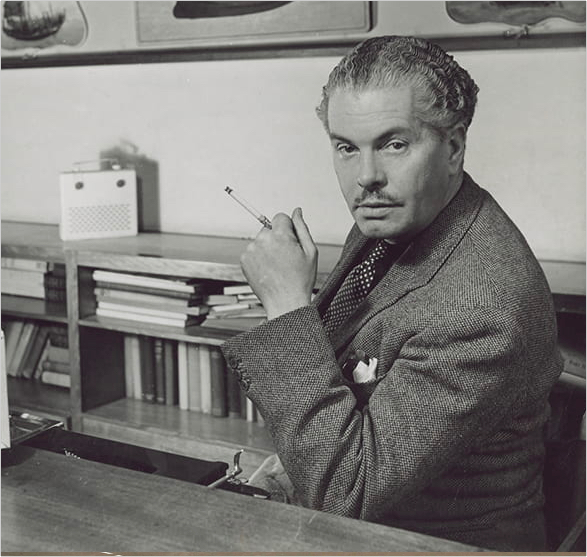

Wells Wintemute Coates OBE (17 December 1895 – 17 June 1958)

Coates was a key figure in the development of the first phase of British Modernism. A Canadian national brought up in Japan he seems typical of the invigorating spirit that entered British cultural life in the 1930s. Energetic, driven, beholden to no-one, capable of a deep idealism whose seriousness was tempered with a great personal charm, groups of like minded individuals naturally formed around him.

British architect Maxwell Fry recorded his first meeting with Coates in 1925:

“Smoothing with one hand his crimped wavy hair and with the other taking a cigarette from his mouth in sweeping arabesques performed for the theatrical pleasure of it, he surveyed me […] for what I was and what I might be worth to him, and deciding in my favour gave me a conspiratorial wink. In a matter of days we were boon companions.”

Fry and Coates shared ideas that extended far beyond the realm of architecture. The past was moribund, and its traditions fatally compromised by war and economic chaos. In Modernism they found a true enlightenment project, founded on the idealistic belief that reason and rationality were common to all humanity, and that these forces had the capability to transform the world not just in its architecture but in all forms of social, economic, domestic and personal life. The new world would have no emblem or logo, its ethos would be scientific and its aesthetic would be pure form and line. A new mentality would be founded on this essential geometry.

Coates’ seemed ideally suited to the new aesthetic, he was a naturally gifted designer and his engineering background saw those gifts embedded in a practical understanding of the relation of material, function and form. His place in 20th century design would have been assured without him ever becoming an architect.

His work in the early 1930s was both highly radical and commercially successful, producing outstanding new interiors for flats, shops, exhibitions, factories and new BBC radio studios in London and Newcastle. Maybe it is the greatest accolade for designers that their work becomes so successful that it comes to stand for the period in which it was made. Wells Coates’ EKCO model 65 radio of 1931 is one of those objects.

The originality of his designs spring first of all from the properties of the new materials then coming widely into use, Bakelite, moulded plywood, tubular steel and of course re-enforced concrete. His upbringing in Japan certainly provided inspiration and he was familiar with the work of Corbusier. But his influences also point to the Bauhaus and the work of Marcel Breuer. Some of Coates’ designs in tubular steel and plywood could have come straight from the workbenches of this great German design school.

Never the most prolific or famous of Modernism’s architectural pioneers, Wells Coates was probably the most tireless advocate of its cause. His many letters and articles are directed primarily at his fellow architects. Coates established contacts, organised meetings and above all made friends amongst the architects and designers he felt were most in tune with the new spirit. That something resembling a Modernist movement existed at all in Britain is in some large measure down to Wells Coates. He founded the deliberately futuristic sounding MARS group (Modern Architecture Research) to spread the new ideas in the public and architectural realms. And when Siegfried Giedion, secretary of Modernism’s international organisation, the Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne (CIAM), asked for British architects to join the movement, it was Wells Coates who got the call.

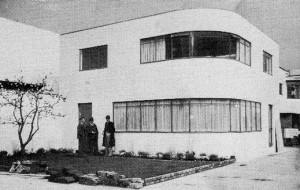

Coates’ first architectural partnership was with a young and idealistic David Pleydell-Bouverie. Few of their “Sunspan” homes were built but in them can be seen another modernism, one with a human scale, without bombast, monolith or icon, and intended for the benefit of all.

In 1931 Coates found an equally idealistic client, Jack Pritchard, with whom he founded Isokon a company altogether formed around the transformative ideas of modern design, producing furniture, appliances and Coates’ first apartment block at Lawn Road in Hampstead completed in 1933 and known as the Isokon Building.

Stylistically similar, the Isokon flats have a much more utopian intent than the unrepentantly commercial venture at Embassy Court. Perhaps the change was a global one. The Soviet and Nazi regimes suppressed Modernism as either too elitist or insufficiently imperial. Modernism vanished from the countries that had given birth to its vibrant and innovative spirit. The fractious, multilingual and overtly political CIAM conferences where Coates met Corbusier, could not, for all their poetics and rhetoric, compete with the stage managed authority of the New York exhibition of the International Style in 1932.

If Modernism was to survive in the mid 1930s it would do so in a marketplace increasingly bounded by perceptions of America. Embassy Court seems to draw from two worlds. American innovations were present in its design, but so is a memory of the “Sunspan” houses. Coates’ next major building at Palace Gate in Kensington leaves a part of this behind. Its brilliantly cantilevered split level interiors were intended once again for an affluent clientele.

But America’s growing dominance was more economic than cultural. In Britain, the influx of Europeans into Britain included world famous architects such as Bertold Lubetkin, Erich Mendelsohn and Erno Goldfinger. These new voices mingled with those already here like Serge Chermayeff and arrivals from the dominions such as Coates. Together with home-grown talent like Maxwell Fry they formed a uniquely British and truly international scene. Rarely before or since, has British design been so receptive, creative or forward looking.

Coates received an OBE for his work on the top secret “Vampire” jet fighter. But the war had changed everything. He failed to find a place in the Corbusier-inspired architectural “brutalism” that took hold in the Britain of post-war reconstruction. But while his post-war career seems to have lacked focus, his drive for innovation lived on. His last significant building in the UK was the “Telekinema” for the Festival of Britain in 1951. This extraordinary building, designed to show large format television as well as stereoscopic films, was intended to last one summer but outlived the festival by 6 years as the first home of the National Film Theatre.

And there were many other projects. He turned his restless and inventive mind to innovative boat design, aircraft interiors, new-town planning at Iroquois Quebec. He was appointed a visiting professor at Harvard, but while he had many minor successes he never achieved the notability he gained at Lawn Road, Embassy Court and Palace Gate. He died in 1958, busy as ever on an urban design project in British Columbia.

Coates’ reputation faded from view and by the late 1970s Modernism itself had become a dirty word, associated with many ugly, crime-ridden and indefensibly shoddy tower blocks of the 1950s and 60s. Perhaps it was exactly the right moment to remember Wells Coates. His rehabilitation started in 1978 with the publication of the superbly researched and written “Wells Coates – a monograph” by Sherban Cantacuzino, then executive editor of the Architectural Review. A steady stream of articles in the national and architectural press followed over the years and his buildings were listed by English Heritage in an effort to prevent demolition. A memoir of Coates written by his daughter Laura Cohn was published in 1999 giving many insights into Coates’ life and personality. His flats at Lawn Road and here at Embassy Court were both been lovingly restored in the first few years of the 21st century. We can perhaps see his achievement now better than for many a year.