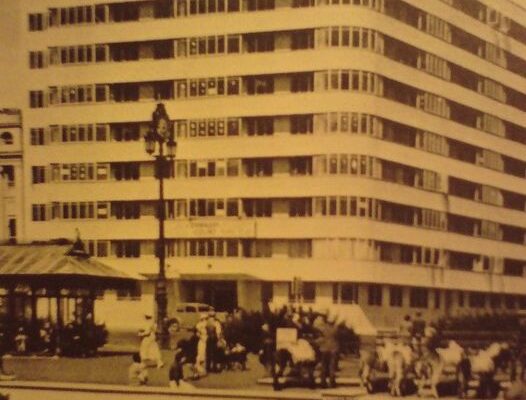

Wells Coates did not initially train as an architect, he produced comparatively few buildings and wrote little to rival the great architectural manifestos of his Modernist contemporaries. Yet he became a hugely influential figure in British architecture and design before the Second World War, and from the 1970s, when Modernism was most loathed as a public architecture, Coates’ reputation was reborn. And that reputation has been soaring ever since. In buildings like Embassy Court it is not hard to see why that that reputation is justified. Its sleek lines and dramatic vistas are indeed achingly beautiful and in its incomparable location on the Brighton seafront, the newly restored Embassy Court is rendered magnificent.

Introduction to Wells Coates architecture

But Coates’ vision was not just architectural, it extended into the experience of everyday life. In light, airy living spaces, he gave us radical new furniture, kitchen designs, right down, as it were, to the doorknobs and bath taps contemporary living. Modernism was not just a matter of different kinds of building, it offered the promise of a different kind of life. And, while buildings like Embassy Court were undoubtedly built for the elite, their promise could be extended to everyone.

In Embassy Court we come into contact with something perhaps sadly missing from British cultural life today; a real sense of the future. Coates’ future was deeply and in its widest sense progressive. It was a future that could throw off the terrors and burdens of the Victorian and Edwardian past and today still gives us a vision of something wonderful; a world of light, space and fresh air, places in which to live and breathe, to think afresh and once more dream great dreams.

Coates’ reputation faded post-war but his rehabilitation started in 1978 with the publication of the superbly researched and written “Wells Coates – a monograph” by Sherban Cantacuzino, then executive editor of the Architectural Review. A steady stream of articles in the national and architectural press followed over the years and his buildings were listed by English Heritage in an effort to prevent demolition. A memoir of Coates written by his daughter Laura Cohn was published in 1999 giving many insights into Coates’ life and personality. A later assessment of his work was published as part of RIBA’s Twentieth Century Architects series in 2012. “Wells Coates” by Elizabeth Darling puts him definitively in the firmament of most significant figures in British Modernism. This book contains rather more on Embassy Court than earlier publications. His flats at Lawn Road and here at Embassy Court were both lovingly restored in the first few years of this century. We can perhaps see his achievement now better than at any time in many a year.

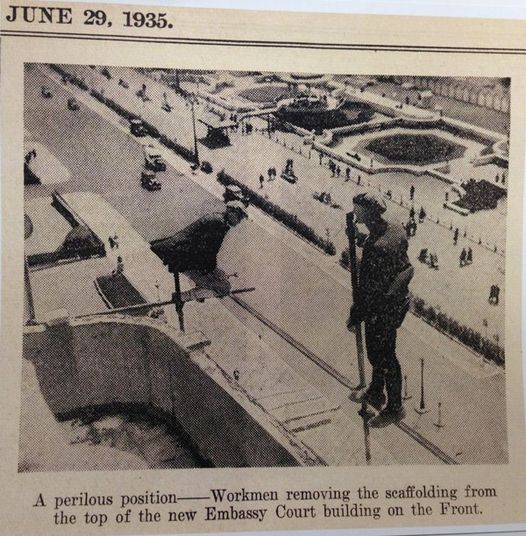

Embassy Court's Construction

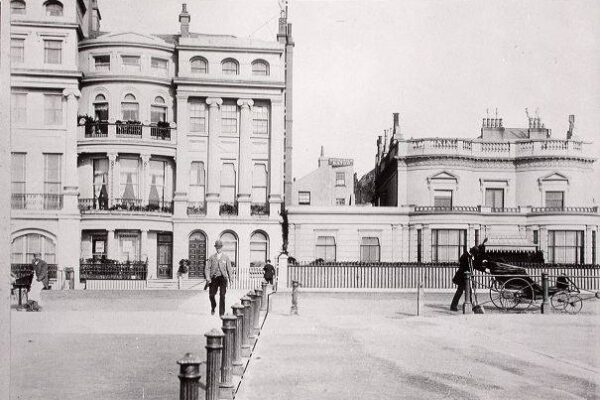

At the junction of Western Street and Kings Road on Brighton seafront, just on the Brighton side of the ancient parish boundary between Brighton and Hove, stood a 19th-century villa called Western House. Owners included Waldorf Astor, 2nd Viscount Astor and the drag king Vesta Tilley.

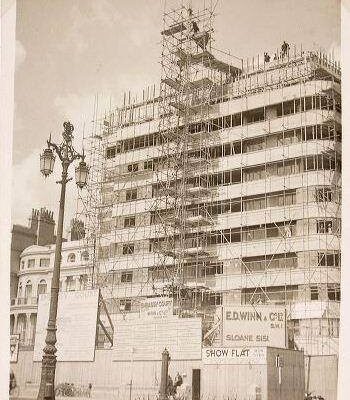

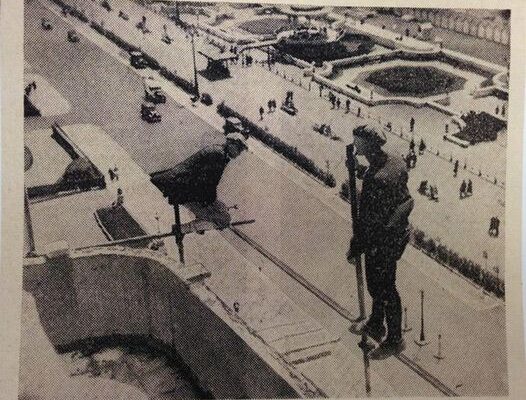

In 1930 the site was chosen for redevelopment and the building and its grounds were demolished. Nothing took its place immediately, though, except for a temporary racetrack and miniature golf course. Developers Maddox Properties acquired the site and in 1934 enlisted Wells Coates, a Modernist architect responsible for the striking Isokon building in London earlier that year, to design a block of luxury flats as a speculative development. Embassy Court was completed in 1935. Its reinforced concrete structure and steel-framed doors and windows were distinctive features, and other facilities included a ground-floor bank, partly enclosed balconies to every one of the 72 flats, and England’s first penthouse suites. These occupied the top (10th) floor; with a sun terrace on the roof. The other ten storeys had seven flats each. Each flat was “all-electric”, including the space heating in the form of ceiling panels. A constant hot water supply was achieved by generating and storing it in a thermal energy storage system in the basement. Coates commented: “Old ideas have been discarded and a new building has arisen to greet a new age that thinks of happiness in terms of health”.

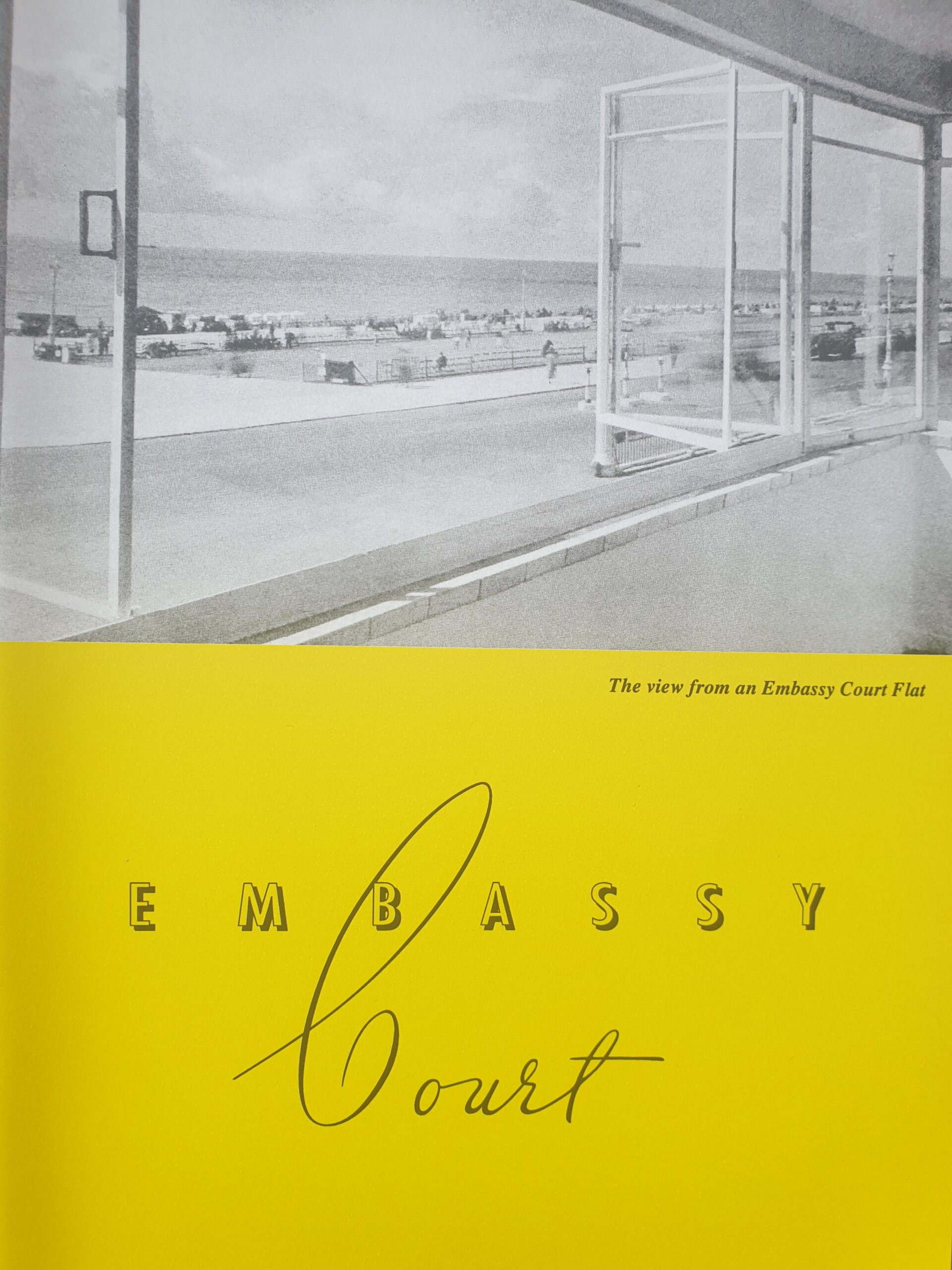

Original sales brochure, reproduced and available on tours

Through the 20th Century

All 72 flats were initially rented out rather than sold to owner-occupiers. Rents varied between £150 and £500 per year—expensive for that time, and similar to the cost of a house in Brighton. The ground-floor bank branch lasted until February 1948, when it was converted into a restaurant; this was only in use for five years. Major renovations were then carried out in the 1960s: new doors, windows and lifts were installed.

The building’s high-class status declined from the 1970s when the freehold changed hands frequently and many flats were acquired by absentee landlords. Many leaseholders built up long-term rent arrears, and lack of clarity over ownership made raising money for refurbishment difficult. Embassy Court gradually fell into disrepair. The freeholder until 1997 was a company called Portvale; it was put into liquidation when a court case resulted in a demand to spend £1.5 million on maintenance. The Crown Estate Commissioners then took possession of the freehold, but Embassy Court’s leaseholders established a company, Bluestorm Ltd, to buy it; this was achieved after another court case.

Bluestorm’s position was strengthened by the Commonhold and Leasehold Reform Act of 2002. In a landmark ruling the former freeholders lost their case against Bluestorm at the High Court of Appeal in February 2004. A mere 14 months later the restoration of Embassy Court was complete.

Decades of leasehold reform are enshrined in the story of Embassy Court and it is a mostly refreshing example of the real effects of successful legislation. It is also a wonderful example of what can be achieved by ordinary people acting collectively in the common interest.

Refurbishment

The first plans for refurbishing the building were announced in April 1998. The leaseholders’ association commissioned local architects Alan Phillips and Matthew Lloyd to undertake design work and Ove Arup and Partners for their structural engineering expertise. Work was expected to cost £3 million to £4 million, of which a grant from the Government’s Single Regeneration Budget would have covered £1.4 million. The project depended on the Sanctuary Housing Association acquiring the leases to 26 flats and the Crown Estate Commissioners transferring ownership of the freehold to the leaseholders’ association. The proposed work was described as a “complete refurbishment” and would have lasted until 2000.

This plan fell through though, and the building continued to deteriorate. Architect Alan Phillips, who had continued his association with the building during the “impasse in negotiations” which had characterised the previous three years, described Embassy Court as being “on the cusp between demolition and renovation” at a debate in November 2001, at which he announced a new plan to convert the lower storeys into a hotel. Money generated by this could then be used to improve the upper storeys, which would remain residential. The nearby Bedford Hotel provided a model of a mixed-use tower block with hotel accommodation below residential flats.

Another court case began in November 2002. Bluestorm and Portvale Holdings made claims against each other in relation to paying for the building’s restoration. By this stage Bluestorm estimated the cost of a full refurbishment would be £4.5 million. Portvale Holdings stated it intended to sell the flats it owned, and a former director of the liquidated Portvale company later stated he did not wish to buy the freehold back from Bluestorm. The case was adjourned after two weeks and was decided in March 2003 in favour of Bluestorm. The chairman of Brighton and Hove City Council said he “welcomed the decision”. Portvale Holdings appealed against the decision in February 2004, but a judge at the Royal Courts of Justice upheld the original verdict. This brought to a conclusion a long and complex period of legal action; the judge observed that the ongoing battles between leaseholders, landlords and freeholders had been “more suited to a nursery school playground”.

In July 2003, Bluestorm announced a new refurbishment plan, this time involving Sir Terence Conran’s Conran Group architectural consultancy. The scheme architect was Paul Zara. Conran Group undertook a structural survey which showed that the concrete walls had not deteriorated as badly as expected: its director said that the building was in “a very poor state [but] perfectly salvageable”. The expected cost was £5 million, and various sources of funding were proposed: money received from Portvale Holdings and from the leaseholders was to be used alongside National Lottery and European Union regeneration grants for which Bluestorm would apply. No grants or Lottery funding were ever received. Also commissioned alongside Conran Group were structural engineering firm F.J. Samuely, whose founder Felix Samuely had worked on the building originally, and some other specialist companies. By September 2003, Conran had assembled a working group of engineers, designers and other professionals, and the plans included provision of a swimming pool and public facilities such as a restaurant, museum and art gallery by making use of underused areas of the building.

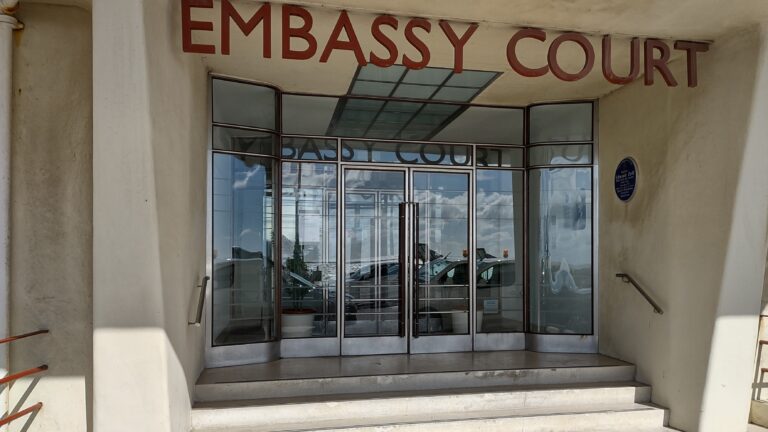

Work began in December 2003. First, the communal areas and lobby were deep-cleaned and exterior hoardings were put up; other early priorities included new electrical and heating systems. The overall timescale of the project was stated to be three years. At that time, the leaseholders were told they would have to fund the entire £5 million estimated cost themselves: some would have to pay around £100,000+ each. Also, the project leader indicated that the planned swimming pool, art gallery and other new features would be “put on hold until 2007”. By February 2004, the bulk of the work was expected to start in summer 2004. Bluestorm raised a planning application, and Brighton and Hove City Council granted outline permission in June 2004. New windows, doors, plumbing and heating, repairs to the concrete structure and re-rendering the exterior were all prioritised at this time.

The first part of the refurbishment project was completed on time and on budget. After a delay caused by poor weather, the exterior hoardings and scaffolding were removed in early April 2005 to reveal new windows and a “smart cream concrete façade”. The second phase involved repairs at the rear, the promised replacement plumbing and heating systems, new lifts and new front doors, and was due to finish in September 2005. The longer-term proposal for a basement swimming pool remained, and other ideas suggested at this time included a gymnasium, reinstatement of the original 1930s foyer decor including a mural by Edward McKnight Kauffer, and the conversion of one flat into a 1930s-style showpiece. Bluestorm organised a party on the Brunswick Lawns outside Embassy Court in September 2006 to celebrate the completion of the work. Local record label Skint Records led a separate private party on the top floor of the building. Public tours were also conducted later in the month. The earlier problems of poor security had been overcome, and Embassy Court was no longer “a haven for drunks, drug addicts and homeless people”.

With the investment of £5 million, raised entirely by the residents, Embassy Court was overhauled: by 2006 it had been restored to its original status as a high-class residence, in contrast to its poor late-20th-century reputation.

Read a review of the finished project in Building Opinions

Of course time marches on and the unforgiving nature of life on the seafront means that continual maintenance is required to keep up appearances. Scaffolding frequently adorns the building to enable repairs and decorations as can be seen from our drone footage.